Back in 2012, McLaren presented one of the most hotly anticipated cars of recent memory; a spiritual successor to the legendary F1 that became known as P1. But while the first glimpse most of us got of that car was just over a decade ago, the conception and development of it began closer to two decades ago. And the man leading its evolution was Dan Parry-Williams. As rumours of a successor to this groundbreaking hypercar gain traction, we look back on the development of the P1, told through the personal insights of its Chief Designer.

“I got a phone call back in 2007 and the caller, who turned out to be a headhunter for McLaren, actually said ‘how would you like to design the next McLaren F1?’ which is exactly the type of phone call you want to receive,” says Williams. From late 2007 and throughout 2008, while much of McLaren Automotive product development was focused on the 12C and Mercedes-McLaren SLR, Dan had the rare opportunity to creatively explore all avenues to deliver a simple brief. “Really the only direction I was given was ‘create the ultimate car for road and track,’” he remembers.

Creating the ultimate car for two very different scenarios required a transformative leap in automotive engineering and design, quite literally. Dan came up with the idea of a ‘transformer’ car, able to switch personalities with a raft of active aero and active suspension. It’s a common enough idea in 2024 – and in fact, rumoured to be a major component of the P1 successor – but in when the P1 concept first appeared in 2014, it was revolutionary.

“The unique, groundbreaking achievements in the P1 really surrounded this idea of it being a fairly comfortable, quiet and easy to drive car with luggage space, as well as – at the touch of a button – a seven-minute Nürburgring lap car. The active suspension could drop the car down from a 120mm ride height to about 60mm, and then we’ve got proper ground effect in a road car, as well as a hidden active front diffusers and a huge active rear wing. There was nothing else like it,” he says.

Such grand ideas are no surprise given Dan’s background. Chief Engineer on the Jaguar XJ220 project; a whole host of OEM projects at TWR, including the original Aston Martin Vanquish concept; Head of R&D for Arrows F1 team. In the worlds of both motorsport and road car production, he had worked at the pinnacle and there was a clear vision on what he wanted to achieve with the P1.

“Initially I proposed the P1 should have a totally different architecture [than the 12C], with a biplane rear wing, fixed seats, raised footbox and a narrow bubble glasshouse with storage behind the rear seats. But cars, even at this end of the market, are a political exercise and it’s never a straight line to production. You have inputs from stylists, budget-holders and engineers and your job is to take all of those inputs and ensure the car doesn’t deviate too much from its original mission,” says Dan.

“We had, for example, started with a naturally aspirated engine. Then it became a variation of the twin-turbocharged V8 in the 12C and then we explored hybridisation. But at that time every electrification component was too heavy and not powerful enough. Then once we’d seen the Porsche 918 concept at Geneva, we knew we had to look again at hybrid power for the P1. The logic was always sound – a generous dose of extra power and the feel of a naturally aspirated engine – but we just needed to make sure it came without compromise. With the help of McLaren Applied Technologies and a new start-up battery company, the P1’s hybrid powertrain concept took shape.”

As the mechanical specification came together, Dan developed what he called the ‘ugly duckling’ surface model for the P1. A car that was shrink-wrapped around the powertrain and components and exhibited the ideal aero characteristics, but then it had to be made beautiful. He explains: “We had Rob Melville working on a theme for the final design and Paul Howse also working on a theme, as well as an incoming Design Director – Frank Stephenson. In the end, Paul’s design was deemed the most beautiful and I think most in-keeping with the original philosophy of form follows function, free from excess and super shrink-wrapped to maintain things like that pared back frontal area.”

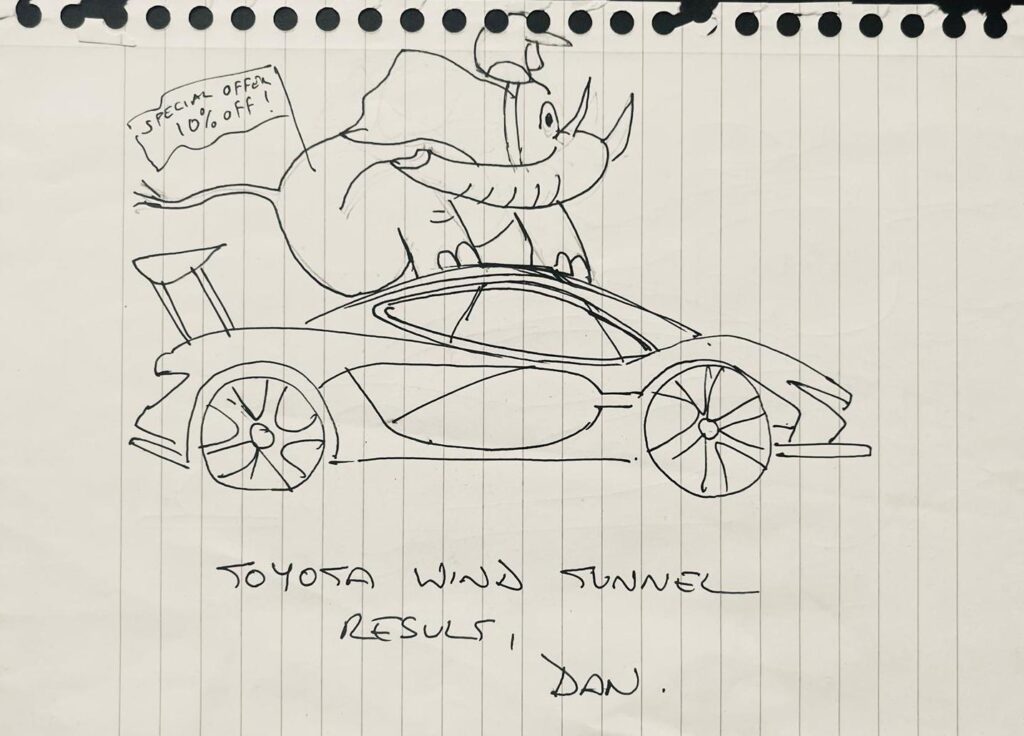

Delivering the P1’s aerodynamic performance was really breaking new ground. Nothing like this had ever been attempted before, so the team had to take the finalized design and begin a rigorous programme of simulation to ensure it could achieve the high top speeds while also managing the 600kg downforce figure.

There was a lot of CFD (computational flow dynamics), which informed the production of a 40% wind tunnel model, tested in the same wind tunnel as the McLaren F1 team was using at the National Physical Laboratory in Teddington, UK. With just a final few tweaks – the addition of some inlets ahead of the front wheels – a full-scale aero model began testing for the final validation. ‘The ultimate car for road and track’ had taken shape.

“About five years after I got that first phone call, we presented the P1 at the Paris Motor Show, complete with an engineer under the stage operating the rear wing on demand. Then in 2013 we delivered the first customer car, and watched as the world became enraptured by our entry into the hypercar holy trinity.

Compared with the McLaren MP4-12C, with which the P1 shared a basic architecture and basic engine layout, McLaren’s hybrid hypercar achieved 50% more power, 300% more downforce, lower drag and weighed 80kg less – even with the addition of the 200bhp hybrid powertrain. And that’s a powertrain which, incidentally, was squeezed into the same wheelbase as the 12C; a car that was already extremely tightly packaged. Those numbers give you just a taste of the extreme engineering that went in to every single aspect of the P1. As does its sub-seven-minute Nürburgring lap time, which remains fast enough to be in the top-10 list for road-legal cars even today. It truly is a ‘transformer’ – true to that vision that Dan had laid out almost two decades ago.

It’s hard for me to look at it objectively, clearly, but I’m proud of the car that we delivered as a team. I think it stands above the other cars in that holy trinity of the time simply because

Porsche may have got it slightly wrong – the battery was too big and too heavy – and Ferrari really kept the V12 as the centerpiece with a nod to hybridisation with a small e-motor. I feel like the P1 was the most compelling in its execution, but time – and the market – will be the best judge of that.”

LaSource McLaren Market Analysis

James Banks, Founder of LaSource

Interest in the McLaren P1 continues to evolve and grow as the market realises that its lightweight plug-in hybrid formula established a trend that it still being followed today, including with the likes of the Bugatti Tourbillon. Early battery issues have been rectified by new innovations from the factory, and P1 examples coming to market over the past year have continued to set new record prices. It remains a car with plenty of investment potential over a five-year period and beyond.

Elsewhere in the world of McLaren, the MSO HS and 675LT are the shining lights among the early Ron Dennis-era McLarens. In the Venn diagram of purity, engagement and value, the 675LT remains perhaps the ideal combination, evoking the kind of road-ready track-focused experience of a 911 GT3 RS but with an additional level of rarity. The MSO HS takes things a step further, mechanically very similar, but even more focused thanks to tweaks from MSO and a production run of just 25 units. Every serious McLaren collector has one in their garage, so it’s worth paying attention when one comes to market.

From the more recent era of McLaren, the Senna appears a solid investment. I always talk about cars with purpose and rarity growing in value, and the Senna has both attributes. Only 500 were built and it’s about the most extreme McLaren driving experience you can have, and those few cars that have made it to market recently are showing clear signs of an upward trajectory.